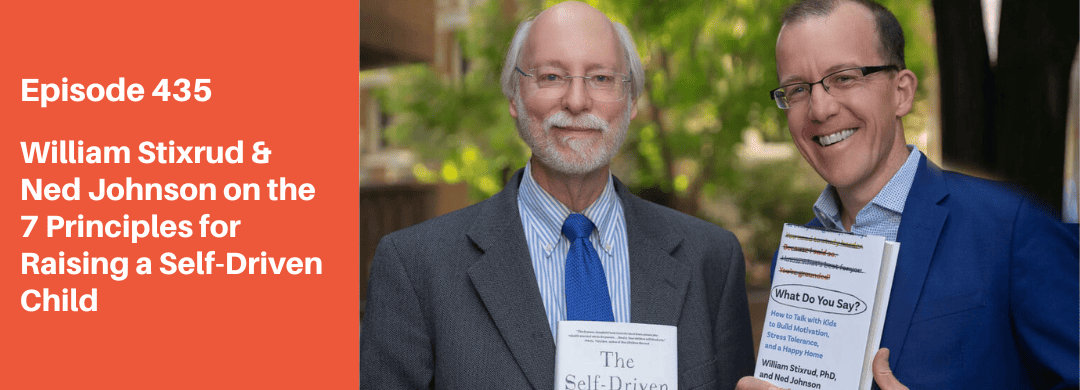

Dr. William Stixrud & Ned Johnson on the Seven Principles for Raising a Self-Driven Child

I’m thrilled to welcome back two favorite podcast guests and just all around wonderful humans, Dr. William Stixrud and Ned Johnson. You might know them from their bestselling book The Self-Driven Child, which I often refer to on this show as one of the most important resources in my parenting life. Well, Bill and Ned have a new phenomenal resource that I can’t wait to share with you — a workbook based on their beloved book called The Seven Principles for Raising a Self-Driven Child.

Today’s episode features a rich and deep conversation about some of the concepts they support parents in navigating in their new workbook, like why fostering autonomy is key to motivation, emotional well-being, and long-term success, why connection matters more than control, how to support our kids without trying to change them, and ways we can create a home environment that builds confidence and trust. They also share practical strategies for effective communication, including how to guide our kids through challenges without adding pressure or anxiety. As parents, it is scary to let go of control and to trust our kids to navigate their own problems, but as you’ll hear in this conversation, this is exactly what they need to be motivated. We know we can’t change them, but we can support them in finding the reason to change for themselves.

About William R. Stixrud, Ph.D

William R. Stixrud, Ph.D., is a clinical neuropsychologist and founder of The Stixrud Group. He is a member of the teaching faculty at Children’s National Medical Center and an assistant professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the George Washington University School of Medicine. Additionally, Dr. Stixrud is the author, with Ned Johnson, of the nationally bestselling book, The Self-Driven Child: The Science and Sense of Giving Your Kids More Control Over Their Lives, What Do You Say: How to Talk with Kids to Build Motivation, Stress Tolerance, and a Happy Home, and The Seven Principles for Raising a Self-Driven Child: A Workbook.

William R. Stixrud, Ph.D., is a clinical neuropsychologist and founder of The Stixrud Group. He is a member of the teaching faculty at Children’s National Medical Center and an assistant professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the George Washington University School of Medicine. Additionally, Dr. Stixrud is the author, with Ned Johnson, of the nationally bestselling book, The Self-Driven Child: The Science and Sense of Giving Your Kids More Control Over Their Lives, What Do You Say: How to Talk with Kids to Build Motivation, Stress Tolerance, and a Happy Home, and The Seven Principles for Raising a Self-Driven Child: A Workbook.

He is a frequent lecturer and workshop presenter and the author of several articles and book chapters on topics related to adolescent brain development, stress and sleep deprivation, integration of the arts in education, and meditation. Dr. Stixrud holds a doctorate degree in Educational Psychology from the University of Minnesota. He did his pre-doctoral internship in Pediatric and Clinical Psychology at the Children’s Hospital of Boston, as a fellow of the Harvard Medical School, and he received his post-doctoral training in Clinical Neuropsychology at the Tufts New England Medical Center. Prior to entering private practice, Dr. Stixrud worked as a staff neuropsychologist at the Children’s National Medical Center and the Georgetown University Medical School.

About Ned Johnson

Ned Johnson is president and “tutor-geek” of PrepMatters, an educational company providing academic tutoring and standardized test preparation. A battle-tested veteran of test prep, stress regulation and optimizing student performance, Ned has spent roughly 50,000 one-on-one hours helping students conquer an alphabet of standardized tests, learn to manage their anxiety, and develop their own motivation to succeed. With Dr. William Stixrud, Ned is co-author of The Self-Driven Child: The Science and Sense of Giving Your Kids More Control Over Their Lives and What Do You Say? How To Talk With Kids To Build Motivation, Stress Tolerance, and a Happy Home, and, coming in March 2025, The Seven Principles for Raising a Self-Driven Child: A Workbook.

Ned Johnson is president and “tutor-geek” of PrepMatters, an educational company providing academic tutoring and standardized test preparation. A battle-tested veteran of test prep, stress regulation and optimizing student performance, Ned has spent roughly 50,000 one-on-one hours helping students conquer an alphabet of standardized tests, learn to manage their anxiety, and develop their own motivation to succeed. With Dr. William Stixrud, Ned is co-author of The Self-Driven Child: The Science and Sense of Giving Your Kids More Control Over Their Lives and What Do You Say? How To Talk With Kids To Build Motivation, Stress Tolerance, and a Happy Home, and, coming in March 2025, The Seven Principles for Raising a Self-Driven Child: A Workbook.

Ned is the host of the The Self-Driven Child podcast. His work has been featured in the New York Times, Washington Post, NPR, The Guardian, Wall Street Journal, US News, Seventeen, and many others.

Things you’ll learn from this episode

- Why empowering children with autonomy fosters their development, motivation, and ability to navigate their own reality

- Why connection matters more than control, and parents should act as supportive guides rather than enforcers

- The role of self-reflection, an understanding of different temperaments, and a willingness to listen without pressure in effective parenting (guiding)

- How to cultivate respectful environments where children feel safe to explore, make decisions, and learn from their experience

- Why raising self-driven children leads to the best outcomes for their lives as self-determined and self-actualized adults

Resources mentioned

- The Seven Principles for Raising a Self-Driven Child: A Workbook by Dr. William Stixrud & Ned Johnson

- What Do You Say? How to Talk with Kids to Build Motivation, Stress Tolerance, and a Happy Home by Dr. William Stixrud and Ned Johnson

- The Self-Driven Child: The Science and Sense of Giving Your Kids More Control Over Their Lives by Dr. William Stixrud and Ned Johnson

- Conquering the SAT: How Parents Can Help Teens Overcome the Pressure and Succeed by Ned Johnson and Emily Warner Eskelsen

- How to Motivate Kids & Build Their Stress Tolerance (Tilt Parenting podcast episode)

- The Self-Driven Child with Dr. William Stixrud and Ned Johnson (Tilt Parenting podcast episode)

- Thinking Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman

- Is This Autism? A Guide for Clinicians and Everyone Else by Dr. Donna Henderson and Dr. Sarah Wayland

- Breaking Free of Childhood Anxiety and OCD: A Scientifically Proven Program for Parents by Dr. Eli Lebowitz

- Recognizing Less-Obvious Autism with Donna Henderson & Sarah Wayland (Tilt Parenting podcast)

- Help for Childhood Anxiety and OCD with Dr. Eli Lebowitz (Tilt Parenting podcast)

- Creating Neurodiversity-Affirming Schools, with Amanda Morin & Emily Kircher-Morris (Tilt Parenting)

- Neurodiversity-Affirming Schools: Transforming Practices So All Students Feel Accepted & Supported by Emily Kircher-Morris and Amanda Morin

Want to go deeper?

The Differently Wired Club is not your typical membership community.

There’s something here for everyone, whether you’re a sit back and absorb learner, a hands-on, connect and engage learner, and everything in between. Join the Differently Wired Club and get unstuck, ditch the overwhelm, and find confidence, connection, and JOY in parenting your differently wired child.

Learn more about the Differently Wired Club

Episode Transcript

Debbie:

Hey, Bill and Ned, welcome back to the podcast.

William Stixrud:

Great to be back.

Ned Johnson:

Thanks, Debbie. We always love talking with you.

Debbie:

Well, I feel the same. you know, I, I, anyway, I know you guys both personally, I consider you friends and colleagues, and I’m also like a fan. So I’m in this really interesting position. but I always refer to your work, The Self Driven Child. Still, I mentioned a lot on my show. It is still such a critical book in my parenting journey. And I recommend it all the time. And when I found out that you were coming out with a workbook related to that. was like, yeah, I need to, I need, I need the workbook and I need to share it with my people. So, you know, I’ve already read your formal bios listeners, go back and listen to the two other visits where we go over Ned and Bill’s last two books. They’re great listens. So we won’t spend a lot of time on that, but if you want to maybe take just a moment to share how you collaborate together, cause I think the two of you working together, it’s such a powerful, dynamic duo and then why this workbook? Like how did this come about? So whoever wants to start.

William Stixrud:

I think that generally what it is is we’ll get some ideas about what our agent or editor will say, you’ve got to write a book about this. Focus on this. And so they’ll start thinking about it, and I’ll do some research on it. And typically, I’ll draft something and do some research on something and send it to Ned. And Ned is incredible at making connections and pulling together and he’s incredibly insightful. We kind of put together the stories that illustrate the principles and we work with a woman who helps us with turning some of the more academic kind of writing into popular for a popular audience and help us with the editing. What would you add, Ned?

Ned Johnson:

You may know the book Thinking Fast and Slow, and I’m not gonna compare us to the Kahneman and Tversky, but what I understand in the writing of that book is those guys would go out as colleagues at university and they just go and walk and they just think about things and they just talk it through. And so as Bill described, he does a ton of research and I just saw this thing and I’ll set it over and we just had a lot of, we think a lot of like, which is great. But we’re also in slightly different, you know, slightly different spaces, slightly different ages. and we’re just just sort of, you know, which is actually, which is great. I mean, it’s great. And so we, we’re just bad ideas around and just, and really flesh things out. I sometimes though joke that I think of myself as being like the color commentator.

William Stixrud:

Slightly different ages. Like a generation.

Ned Johnson:

You know, those give them the play by play and then I’ll jump in with things. like that are Well, they’re entertaining to me and hopefully this somewhat add a little spice to to our writing

Debbie:

That’s great. So, okay. Let me just share the name of the workbook again. And then I want to learn a little bit more about specifically why you wrote this and who you wrote it for. So it’s called the seven principles for raising a self-driven child. And if you’re listening to this podcast as it’s released on this day, the book is now available. And I was so lucky to get an advanced copy and I cannot wait to get my hands on the actual like tactical workbook and dive in, but share a little bit about what you put out there. Because as I said before, we started recording. This isn’t just a self-driven child where you’ve kind of taken everything and just put in a couple of prompts, which again would have value. But you’ve really created such a powerful, I think, tool for parents to really do the deep work which I’m a big fan of, so that they can apply all of these ideas with success and effectiveness in their lives. So talk a little bit about who it’s for and how you wanted to approach that.

Ned Johnson:

I mean, the way that I think about this is, I’ll tell the introduction to the book. When we were first lecturing for The Self-Driven Child, Bill and I were going all over DC, or school after school, after organization after organization. And at some point, Bill took note that there was a woman there who kept showing up over and over and over. And one point he went up to her and hey, it’s really, it’s great to see you, but I gotta ask, you seem to come to everything that we do. And, you know, to be honest, it’s, it’s, kind of the same talk every time. You know, my jokes are the same jokes. Like, why are you here? And she says, you know, I listened to you, Bill, I listened to Ned, and it just makes so much sense. And, and, to be sort of, it’s right not to be on my kids all the time to treat them ways of respectful and less controlling. And then I’ll go out and my kid will do something, you know, so dopey, right? Or I’ll talk to him from some friend who was all spun up and she’ll get me spun up and then I’m back to controlling.

And so I just keep coming back and every time I talk to sort of helps me reset and put things kind of right in my head and right in the world. And the idea behind this workbook is that we’re all homeostatic, right? We all have scripts that we run the past, the patterns that we fall back into. And so while we think the self-driven child is a brilliant insight and treatise on how to live one’s life, the reality is that we can take a great idea from Debbie, a great idea from Jess or Tina or you know any of us but then making that making great thinking becoming great practices It isn’t always easy. And so the idea of this is for exercise and reflections to really take what we think is some better thinking and and Operationalize these and make these better practices. So it’s reflections. They’re exercises. They’re all these kind of Post It ready quotes like let us, you know, put this all over your eyes, put this on your refrigerator or your bathroom mirror, just to remind people and help people make these things practices for them and their families.

William Stixrud:

Yeah. And I’ll just add that The Self-Driven Child, I think it sold a million copies around the world now. Because this idea of empowering kids to have a sense of control over their own lives, it’s really a powerful idea. And people all over the world want things to feel more in control. How do I help my kid with that? And yet, both our first two books are 300 pages. There’s a lot of science in them and there’s a lot of practical stuff too. But nobody ever asked us about the last three chapters in the book. And so what we wanted to do was to kind of distill our best thinking from really both our books into a book that is based on principles. Because I’ve been thinking lately about what we talk about in The Subdriven Child, the four postulates of motivation, which is that you can’t make somebody do something against their will. You can’t make them want what they don’t want. You can’t make them not want what they want. And you can’t make them do things. If you try to change them without their permission, you get conflict and resistance. And these are literally true, but they’re hard to grasp. They’re hard to accept. And I think that our mission for this third book was to make it feel as safe as possible and as right as possible, to move in this direction of supporting your kid by the time he leaves home, or she leaves home, or they leave home to run their own life. And so that’s kind of the short, practical, there’s not a lot of new science in it. But based on principles, that we can, if you ground yourself in principles, I hold these things to be true. These are things that are gonna ground me. It’s a lot easier to apply the practices.

Ned Johnson:

They’re not self-evident, but they are evident.

William Stixrud:

Well put, my friend, yeah.

Debbie:

Yeah, this idea of principles, it is something I wanted to dive a little deeper into. Because you introduced seven and later on in the conversation, I’d like to go through some of them in more detail. But say more about that and actually maybe in how you shaped the book or went about trying to distill The Self-Driven Child and what do you say into this really practical and as you said, operational experience for readers.

William Stixrud:

But we figured that we had already written two fairly long books. And people can always refer back if they want more science, if they want more, they go back and reread those. But we just felt that we want something that’s really accessible. People increasingly are reading less and less. And we just want something that’s accessible, that’s practical, and that allows you to, I mean, the pushback that people give is that, well, You know that if I give my kid more control, I get more anxious because I feel I have no control and a little sense of control is most stressful thing you can experience. you the people said this wasn’t the way that I was raised or my parents say I’m spoiling my kid. But that kind of stuff. And we just want exercises to help people work through that and kind of align the way they’re raising the kids with their own values. And so I think what we did was we thought about what are really the most important things that we teach people that seem to be helpful to people. And then how do we prioritize these? How do we sequence them in a way that people can access this stuff? And it’s just when people apply these principles, it just works because they’re grounded in the reality in part that really is your kid’s life, you know, and you can’t make them do stuff. And it’s hard. We initially had 10. That’s too many — people can’t remember 10. And then we organized it to be seven and try to indicate in the book how they’re related to each other. Just make it easier to understand and see it not as just one little technique, here’s one technique, but it’s kind of a more coordinated whole.

Debbie:

Okay, so The Self-Driven Child came out in 2018. It’s the same year that my book, Differently Wired, came out. My book has not sold a million copies, so I’m kind of in awe of you guys. But I’d love to know because the world has changed.

Ned Johnson:

China is part of it. So I’m not a big deal necessarily in my workplace or my home, but in China I’d be a really big deal. So I may move.

William Stixrud:

Being popular in China helps. There’s a lot of people there.

Debbie:

Wow, that’s fascinating. Okay, super interesting. But thinking about what has happened in the world since 2018, we’re now in 2025 in terms of kids’ mental health, in terms of, well, of course, COVID. And we don’t need to go down a deep rabbit hole with this, but I’m just wondering when you re-approached this subject matter and the themes for this book and really started to think about what are these key principles? Was there anything that you had to kind of adapt or adjust or rethink because of the way the landscape has changed over the past seven years.

Ned Johnson:

Well, mean, certainly probably more quantitative and qualitative changes. I mean, you know, the incidence of mental health continues to increase in ways that are deeply concerning. And everyone’s tried to figure this out. You know, Jonathan Haidt’s book, The Anxious Generation, you know, putting lots of energy into limiting control and regulating social media and access to it by young people. But one of the concerns that we have is as these challenges have gotten more and parents and, you know, educators in the whole country have gotten more concerned about these things. It appears to us that the tendency keeps going towards what we as adults can do or change or frankly control in the lives of young people with the idea of trying to help them be better. And we just really think that, you know, in many ways that they’ve got, they’ve got the cart before the horse. And if we know that a healthy sense of control is the most important thing you can confer on the young person, in part because a low sense of control is the most stressful thing you can experience. And low intrinsic motivation is a transdiagnostic criterion for mental health disorders that anything that moves away from the direction of fostering the young people a healthy sense of control and autonomy and the brain state that supports it is really, it’s going the wrong direction and it’s doomed to failure. We have a chapter at the end of this book about bringing the sense of control to school because that’s where kids spend most of their waking time. And rather than trying to shift school from a source of suffering as it is for so many young people, we really want to move that in a direction of supporting their autonomy, supporting their agency, and all the good things that come from that. One from their being more well-educated and engaging with school, but also the mental health benefits that come from that. So it’s hard because the culture right now, certainly within the current administration, is more command and control. And we just think it’s going in the wrong direction.

William Stixrud:

Yeah. And I’ll just mention the two things I think for me, Debbie, since 2018, number one, we just become even more sure that this sense of control is a really powerful and wonderful idea. For just a couple of examples, we learned that the studies that looked like the reason that caught it to behavioral therapy helps kids primarily is it increases their sense of control. And then the same thing with exercise and meditation, because you said life is better in perspective. You feel like I’m more competent being able to handle things. Also, the more we just continue to study what motivates people and just this power of intrinsic motivation, what it does to the brain, how differently the brain works when it’s intrinsically motivating. And I think the other thing that’s happened to me is this increasing awareness that as Ned said, for so many kids, especially once they’re teenagers, school is the major source of their suffering. One of our friends did a study in three Ohio high schools, and asked kids that kids are really high levels of anxiety and depression, predictably. And he asked them, what are the major sources of your stress? And the top 12 all had to do with schooling and academic pressure. And had nothing to do with social media, had nothing to do with bullying or online bullying. It all had to do with academic stuff. And I would say that the major thing for me was thinking now that schools have increasingly less recess, less play, more instructional time, more AP classes. And a 10th grader taking two AP classes sleeps less, an hour less than 10th graders who don’t. And I just think we have a toxic system here in our honest attempts to educate kids and get them prepared for the world. But we’re moving in the wrong direction. As Ned said, the energy is going the wrong way. So I think there’s two major things for me.

Debbie:

Yeah, thank you. Yeah, and I couldn’t agree more that the timing for this book is so critical and that we are moving in the wrong direction. And so this feels exciting to me to get this into the hands of people. And I did love that. I love a good appendix, like full disclosure. But, you know, the appendix that you had at the end about practicing and creating a sense of control in schools, I thought was so good because you are thoughtfully and respectfully supporting educators, right? You’re not, you know, I recently had Amanda Morin and Emily Kircher-Morris on, talking about their book, Neurodiversity Affirming Schools. And they’re like, we’re not trying to call people out, we’re trying to call people in. And I feel like that’s what your appendix is doing as well. And anyway, so I really appreciated that. So, so important. So I want to go through some of the principles. We won’t go through all of them, because you’re going to have to get the workbook listeners to check it out. But I did, you know, a couple of them, I wanted to touch upon, and just share some things that jumped out at me. The first one was to put connection first. there were some concepts in there that I, that were just, you know, simple, but really like this idea of a window of openness. I’m like, yes, that’s what we need to do is, be aware of when there is a window of openness to, to connect. Right. and as I was reading that chapter, I always try to channel what my listeners would be curious about. just what do you do or how do you advise parents to kind of focus on connection and try to strengthen connection with their kids if their kids really have no interest in spending time with them or shutting them out? Maybe they’re just not good communicators at all and the parents are, they don’t even know where to start.

William Stixrud:

Yeah. And I think that a couple of things we’ve learned since 2018 is that, we just recently learned that close family relationships are more protective of kids emotionally than income or even the safety of your neighborhood. It’s a powerful thing. And I think that closeness looks different for different people. You have a kid who is very extroverted kind of kid and you spend a lot of time kind of going back and forth. You got an autistic kid. It’s a different way of getting close. Certainly there are times in my raising of two teenagers where they didn’t have much interest in me, but I still drove them places. But I brought them home from practices or games. In the evening, they were much more open. They were a little tired. It was dark. They were in the back seat. We weren’t making eye contact. It didn’t feel like a direct conversation. There’s nothing threatening about it. And they just opened up. And that was kind of the window for me. And certainly, I pick up my granddaughters from gymnastics twice a week. And one of them, if it was light, she’d be reading. But I got her dark. And if they aren’t talking, I just talk a little bit about myself. I just tell them a little bit about my day and then they usually respond and bring up something. What would you add?

Ned Johnson:

Well, I think your point about different temperaments. I have, my kids are wonderful, but they’re quite different, right? And my son is as noisy as I am. And my daughter who’s autistic, her communication is different. And oftentimes she doesn’t want to, if she’s sort of burned out, she just doesn’t want more time with me or frankly anyone. But, know, sometimes people feel that. It was funny, I put something on TikTok or whatever, and this dad was saying, my daughter doesn’t, you know, wanna talk with me. And I said, here’s the great thing, to be helpful to her, she doesn’t necessarily have to talk to you, but to know that she can, to know that she can, that alone will help. And so I remember when my daughter would get really, you know, things were going on, and I could see how unhappy she was. Usually after school and I would and I and I was always you know making about me I was so worried I’d done something wrong and I said, you know, are you okay and she’d shake her head and I said I Did is there something I did that that and she didn’t know and said you want to talk about it? Anything I can do right now. No and just shake it. It was all nonverbal. She just shaking her head and so it was clear she did not have the energy, she didn’t want to have a conversation about this. But I felt stuck because I didn’t want to press her, but I also didn’t want to sort of emotionally abandon her, right?

And so I said, so, hey, sweetie, I can see that something’s really going on and you’re pretty upset. I don’t want to press, but I do want to help. Is it okay if I circle back? You know, in half an hour, 45 minutes, just to check in and see whether there’s anything that can help and see that you’re okay. And she’d get this little nod of her head. And I swear to gosh, if I said I’ll come back in 45 minutes, she’d bound downstairs in 30. If I said I’ll come back in half an hour, she bound downstairs in 20. And whatever cloud had come across her had drifted away. And not once did I ever find out what the thing was that she was upset about. Not once. But that wasn’t, it didn’t matter, right? Because we all have things that the imperfect ones, just like meditation, dark thoughts come and dark thoughts go, right? And that’s where we want to be. And so a lot of times I think we as parents feel like we have to be the person to help get our kids out of the funk, to talk them out of the difficult things or the situation they are in. But if we remind ourselves really the ideal thing is that they talk themselves out of it, that they put things into perspective. I don’t try to put things into perspective for them. And we know that this idea being, as we talk about in all these books, and this one as well, being a non-excess presence. And I don’t get upset and try to force her to talk to me, but it’s sort of this gentle, there’s not much communication going on, but sort of gentle support as best I can. And then she, that puts her in her right mind. And then she’s able to shift her own thinking, which is really what we want, because there are all sorts of times when I’m not there. And it shouldn’t be about me, it should be about her developing those tools and of course that sense of control as well.

William Stixrud:

That’s a great point, Ned.

Debbie:

Yeah, like so many truth bombs that you just dropped, you know, and a quote that now I’m also going to integrate into my, you know, I have so many scripts from you guys that I use with my kiddo, but I don’t want to press, but I do want to help is so powerful. And the fact that you

You said not once that I actually find out what the issue was is such a good reminder, but that’s not the point. The point and it’s not about us, right? And that is so hard for us as parents because we do want to share wisdom. We want to problem solve. We want to do all these things. So I just appreciate those reminders. Yeah.

Ned Johnson:

You’re sitting there thinking, but I know stuff. I mean, I think about the three of us, But I know stuff. And if we’re currently listening, and of course they do. Of course they have advice, and of course they have wisdom, and of course they have experience, and they want to share all of it. But again, your point, it’s not about us, it’s about this kid.

William Stixrud:

And just to me, you gave them, I think, the two most important messages are that I really care about you. You’re really important to me. Is there any way that I can help? I think that kids, adolescents particularly, they’re biologically driven to move away from their parents and spend more time with their kids and have other kids be the main kind of source of engagement and reward in their life.

And the main thing is that we let them know that even though they want to spend a lot of time with us, they still do things with us, that we still take them places, we still can put something on their bed that we’re thinking they would be interested in. To show that we care about them, that’s the most important thing. It’s just that we’re available to help.

Debbie:

I had my 20 year old home for winter break. This is the first year at university and it was really interesting figuring this out. And of course I want to connect as much as possible. And I also just wanted to just back off and let that time be whatever my child needed it to be. my, not a trick, but my strategy perhaps was, you know, to just put out a jigsaw puzzle because I know that Ash cannot resist that. so, and even sometimes after dinner, like, you know, I’ll be like, do you want to work on the puzzle for a little bit? And I, you know, the response would be, no, I’m going to go upstairs and work on my music or whatever. I’d be like, cool, no problem. But then I’d be cleaning up the dishes and I’d see them wander over and sit down and start working on. And so I’d finish the dishes and I’d sit down. I wouldn’t say a word and an hour will have gone by and we were just quietly working on the puzzle together. And I was like, oh, I will do this. As long as you are willing to puzzle with me, I’m there for it.

William Stixrud:

Yeah, yeah, beautiful.

Ned Johnson:

That’s such a wonderful example and such a beautiful image. because, know, and, you know, especially when, you know, people have different temperaments. My daughter is also a huge puzzler and it’s so hard for all of us, but I mean, for me, most of all, to remind myself that my, what I need and what I want and what fills my cup and my communication style is not my daughter’s, right? She just experiences the world and lives the world differently. And so what I need, you know, to when I can remind myself to pay attention to what she actually wants and needs. And so I love the puzzle. like a picture of a mouse trap with a little puzzle piece rather than there being some cheese on it.

Debbie:

Okay, so the fifth principle in the book is to motivate your kids without trying to change them. And I think this is one of the most difficult things for us to do as parents. I’m sure you’ve talked to parents so often in your work and probably have a lot of experience being on the other end of this as well. Talk about how you approached this chapter in the workbook to help parents really kind of I guess buy into this idea that they can’t change their kits and that there are other ways to go about motivating them.

William Stixrud:

I think that we wrote about motivation in our first two books. And I think that when we write about it in the second book, we realize that so many parents are always asking us, how do I motivate my kid? And we realize that what they’re really asking is, how do I change my kid? How do I get him to do his homework? How do I get him to care about this? How do I change my kid from where he is now to someplace else? So we really looked at the science of change. And every place we look, what we’ve learned is that if you try to make somebody change, you try to change somebody who’s not asking you to help them change, as I said earlier, you get conflict resistance, but only every time. And it’s just true. And as human beings, one of the things we focused on in our second book was motivational interviewing, which is this kind of dialogue approach that’s used a lot in therapy to help people kind of get to find their own solutions to problems. And it doesn’t involve you need to do this, try this, try this. It means just listening, reflectively, I’m trying to understand, because people tend to be ambivalent about virtually anything, about changing in any way. And if we keep saying, you need to do this, you need to do this, they argue, no, I’m not going to do that. Let’s do hard, or maybe I’ll fail, whatever. And so if we stop arguing one side of that ambivalence, we just listen. Eventually, they say, well, maybe I need to change. And we’ve always seen some dramatic examples of that in our own work. Certainly, this kind of approach is used all over the world. And we also thought about this new program, SPACE program, which comes out of Yale – Supported parenting of anxious childhood emotions. It’s a brilliant program for, it’s as effective in reducing kids’ anxiety as therapy for the kid, and it only works with parents. There’s another illustration of the fact that we have a lot of power, we have a lot of influence on our kids, but the SPACE program works by focusing simply on what are we going to do as parents? What do we think is right? What’s the right thing for us to do? And then to do that and not try to change the kid. And so I think that the idea that you really, if you try to make somebody do something, you try to make a two-year-old do something. And they lay on the ground and start screaming. If the idea is getting in the car, you can pick them up and put them in the car. But they aren’t getting in the car. You simply can’t. You can’t make an infant stop crying. You can’t make them eat. And once we make peace with the fact that force doesn’t work, we really can’t make people do things. Force is off the table. Then we’re more flexible. Then we think more flexibly. We find other ways to help to influence people and help them find their own reasons to change.

Ned Johnson:

And the thing I’d add there really quickly is when we take force off the table, the thing more flexible because when we force someone else and they feel low sense of control, by definition, they are going to be less cognitively emotionally flexible, right? Because it’s so stressful, right? So that executive function just goes right out the window, right? So, and so part of, as a parent, we often think, well, gosh, if only they were thinking about this the way that I’m thinking about it, they would agree with me. But some of the reflection exercises in there are to think about how do you as a parent feel when your spouse tells you know, know, for example, they’re, know, Debbie, you know, three cups of coffee, don’t you think two would be enough? And you’re like, you know, buzz off, man. I live in freaking Amsterdam. It’s cold and rainy all the time. I need this. You know, and don’t you think that and no one ever said, Hey, don’t you think you should have cut it down? Like, Nope, I don’t. And you argue in your head all the reasons why, of course, I deserve this cup of coffee. And you know, get over yourself, Ned, because you did anything anyway. And it just, it doesn’t, it doesn’t work. And so the the exercises here were to point out one, take note of what happened when you try to talked your kid into this that the other you know how often what’s that feel like but also for yourself you know if your mother-in-law tells you you should really do don’t you think should you know you know dust a little bit more often you’re like I mean my gosh no one ever like I’m gonna get right on that said no nobody ever.

William Stixrud:

You know, it’s just so interesting because when we were writing the second book, there’s a school counselor who used this kind of listening, this kind of communication technique. It’s really a dialogue technique with one of her clients in school, a school counselor, and the kids stopped smoking pot without any attempt to get the kid to stop smoking pot. I just tested a 15-year-old kid while we’re working on this chapter who was smoking pot all summer. And he was a very good basketball player, and really wanted to make the varsity. And so I sent the mom a draft copy of the chapter. And I said, just try this approach. And she sat down with her kid. They’ve already found his stash a couple of times and got rid of it and scolded him and threatened him. But he kept smoking. And so simply said, tell me, what does pot do for you? And he just told all these, how wonderful he feels, he makes it less stressed, he’s more fun with his friends, and this COVID, and he’s tolerable. And eventually, she got feedback, it sounds like it really does help you feel better. And he says, yeah, eventually he says, yeah, but I can’t make myself practice as hard as I need to make the varsity in the fall. And by the end of summer, he wasn’t smoking pot. And that’s when kids voice their own reason for change. And I was just so struck that a parent with no training, because this isn’t rocket science. This is really simple stuff. You just ask kids open questions, listen to the response, let them know you’re trying to understand. And so often, eventually, because they don’t want to suffer, they don’t want their life to work, they kind of figure it out. And I think that the example you gave with your daughter, you let her know, I care about you. Then you gave her space. And she’d bound down 20 or 30 minutes later, have him figure it out herself, which is exactly what you do. It’s exactly what we want. It’s to solve their own problems.

Ned Johnson:

And what I hope people get when they go through this, we have a whole exercise where you take basically any issue and you can articulate the reasons why, you know, if I, you know, work harder, you know, and do more homework, I’ll get better grades, I’ll get better college choice, I’ll get better. My teacher will think I’m, you know, sharper. You know, my parents will get off my back. You can come up with a hundred reasons why I might want to engage more in school or whatever the thing is. But there are also all these reasons on the other side. And what happens is when we, and we, think we can all recognize this. When we argue one side of the equation, our kid will argue, yeah, but, yeah, but, yeah, but, yeah, but, and they’ll just, and they’ll fight back. As opposed to taking, taking up our side. And then the real challenge as I see it is all those wonderful reasons that are all valid and true. And that’s why we as parents make them. They become poison pills. And so the kid has to come up with, if he eventually changes his mind and says, I do want to study harder or clean my room or smoke less pot or whatever, they have to come up with a reason other than those ones that we’ve given them because they’re tainted. You don’t want to do that.

Debbie:

So many important things that you just shared. And I’ll just say one of the questions I get the most of in this community is starts with the seven words, how do I get my child to…? And my answer is always the same. You can’t get your child to do anything. Like we can’t control another person. And I have a lot of evidence that that is true because I’ve tried for many years. But again, what you mentioned, Ned, is what I appreciated so much about these principles, about this principle in particular was the questions that you guide parents through in that chapter really do help the reader feel like how terrible it is when someone else is trying to control you. The challenge then is to look at our kids as creative and resourceful and whole humans and really, you know, that’s not so easy to do in a culture where the norm is about compliance, right? And that is being reinforced more and more, I think, every day, unfortunately. but that to me that just stood out as an example of why this workbook, I think, is so powerful because when we can really then feel that embodied sense of another person trying to control me, then we can be like, that’s what my kid’s experiencing too. And that then gives us motivation to show up in a different way to that dynamic.

Ned Johnson:

Yeah, I appreciate that. I just keep just thinking, rereading this this morning. And just thinking, you know, if I’m trying to get in, if I’m trying to get in shape, right, you know, for the holidays, I eat every carbohydrate that was available to me right and think, right. And if I’m sitting down to dinner and my wife say, you know, there’s an off the big piece you just took there. Right. What would my reaction be? I mean, go pound sand. Right. And the challenge is I want to, you know this is the time everyone wants to be getting more fit. I already have that motivation, right? And the thing that’s so interesting is when we use these approaches and we’re respectful, it goes back to the connection they’re asking, talking about before Debbie, it deepens our connection because we feel more connected to people who treat us respectfully. And here’s the thing that’s fun, that closeness, that relationship is one of the core attributes of intrinsic motivation. So treating me respectfully makes me want to then do the thing. And here’s the real fun kicker. We as humans and our children especially are most likely to buy into our priorities, our values, the closer they feel to us. Even if they don’t, I don’t really love that sports team or I don’t vote that way, whatever, they’re much more likely to slide in our direction when they feel close to us. the whole, mean, they all kind of have these wonderful feedback loops on one another.

William Stixrud:

Yeah, that’s a point.

Debbie:

Yeah. Well, I think we’re going to wrap up. We won’t go through everything, but I do want to just highlight that you have a principle on being a non-anxious presence for your family, which is one of your kind of core concepts that runs throughout all of your work, which I love. And the last principle was to encourage radical downtime, which I really appreciated. And then, of course, that meaty, awesome appendix for educators in schools that I thought was fantastic. As we wrap up, is there anything that we didn’t touch upon that you would want listeners to take away from this conversation who are inspired perhaps to really do this work and dive in and see how it can change their relationship with their child and maybe get results that will feel better for the whole family?

William Stixrud:

The one thing I’d say, Debbie, is that one of the things that strikes us, I think increasingly, is how delusional the thinking is about what it takes to be successful and happy in this life as kids grow up. I mean, we’re just constantly talking with kids who basically think, I am my grades. That the most important outcome of my whole childhood and adolescence is where I go to college. If I get into a good college, my whole life is set. And it’s just delusional because it’s so out of touch with reality. And I think that we have a chapter in this book on helping kids grow up with an accurate model of reality, of really what it takes to create a life for yourself that’s meaningful. And for us, the kids who grew up to think I’ve got to maximize potential. And our angle is you maximize your potential by creating a life that you’re happy with. And so I think I really like that chapter and the focus on happiness and what really makes people when 20 years ago, they started studying happy people as opposed to just people who have anxiety and depression stuff. They really studied what makes people feel happy and fulfilled and just give a sense of well-being. And we know there’s a whole science to it now and kids don’t have any clue about it. The kids get into elite universities. I tested two kids in the same week, high school seniors, both got into college and I said, and they’re both on medicine for anxiety and depression, really high achieving kids, really elite schools. I said, are there times when you feel happy? And they both said, independently they both said, I felt happy the day I got into college. It lasted one day. They get into Yale, they’re miserable at Yale, Yale didn’t do it. And so I like the focus in that chapter on helping us understand there’s so many ways to make your way in this world, to find a place for yourself in this world that’s meaningful, that’s purposeful. it’s just, the kids have this, we don’t, this very narrow lens, this very narrow path, it’s just wrong.

Ned Johnson:

I would sort of fold into that point that you asked about, the point you made a moment ago, Debbie, about the idea of non-anxious presence. And part of what happens, I think, for kids and also for us as parents, when we imagine this certain path to nirvana, right? If our kids stay on this path, we’re going to have a world where they always turn to the sun and the moon.

And we worry if they’re not on that path, all these great things that they won’t have, as opposed to thinking about all the other experiences that they will have. And for folks who have listened to our conversations with you before, may recall that I told the story before about my daughter, who was in eighth grade, was three months full school refusal. Now I’m a guy who helps people get into college, like what’s my inner monologue? And so I’m in this space because I do all this work built around these books. On the other hand, I’m like, I do think about college a little bit, right? And so much, so much of the point we make is so much of our work is on ourselves, right? Not on our kids. And so I’ve never meditated more in my life than I did those three months. You know, I fortunately had somewhat of a lull in work so I could, I could sleep more and I can exercise more and, and just really had to take a long view. And so fast forward my daughter’s in her second year of college now at age 19 got diagnosed with autism which explains a lot of what was hard for her in eighth and seventh and eighth and ninth and tenth and eleventh and twelfth grade. And she’s doing great. I mean, she’s just this incredible human And the friend who was a therapist, you know said it’ll be interesting to see what Katie Johnson decides to do with that Remarkable mind of hers when she figures out what she wants to do and she didn’t know for five, because she didn’t for five years, she really didn’t know who she was. So it’s hard to know who I want to be and how I contribute. And, you know, I think we as a family did a pretty good job of saying, you know, we love you no matter what. And it’s your work, we’ll help you, but it’s your work to figure out what kind of thing you want to do? And where do you want to live? And it’s nice to be able to report, as it is for so many kids who struggle, that she’s on the other side and their life is not perfect. You know, her standards, but man, is she doing great. And so much of part of this workbook is also just to help parents feel, to develop a practice of knowing that, feeling safe to trust their kids and to support them and not be on them all the time. Partly because we weaken that connection with them. And it just doesn’t work, right? So we want, you know, if you can back off kids to be closer to them, not be on top of them, or lead back off to have a closer connection. There’s so many good things that come out of that. And we hope that this workbook helps people move in that direction.

William Stixrud:

Yeah. Yeah. And from our angle, it really does apply across the whole spectrum of neurodiversity. And I’m really happy that in autism now, there’s increasing focus on happiness, the science of happiness, the science of motivation that focuses on autonomy. What people really, what’s important to them because for so many years, the focus with autistic young people was to get them to do stuff. How do we get them to do stuff? And not a focus on who they are as people, what do they care about, what’s important to them. And you’re raising your own autistic daughter, with loving these kinds of principles. It simply works. And she’s thriving as a young adult in a way that would have been hard to predict when she was in eighth grade, right? Nobody knew that she was autistic, including her. I think you’ve had Bill’s colleague, Donna Henderson, on your podcast. And full disclosure, through Bill’s connection that we’ve done, and she did the evaluation for Katie. And at the end of it, said, you know, there’s seven criteria for, and you have to have all three of the social and two of the four of the physical ones. she said, Donna said, for some people, it’s really, it’s kind of, you know, maybe yes, maybe no. She said it wasn’t even close. It wasn’t even close. You could check all seven boxes, but she had so beautifully masked for her entire life. Nobody knew she was autistic, including the people who evaluated her in eighth grade. And of course, including her. And it was so funny because at the end, at the end of it, Donna asked how are you feeling and Katie’s basically floating up in the sky. She’s so happy to have this insight on her. And Donna looks over to her. So how are the parents feeling? And I said, I feel like I’m a character at the end of the movie, the sixth sense. It’s like now, you know, and it all just made, it all made sense. but sometimes in this is, and it’s, the thing that’s, it’s interesting is this, it’s your point Bill works for it. This is not for neurotypical kids. This is not for neurodiverse children. These are, these are all people because they’re, these are all foundational human needs and foundational human tools. So no matter who you are as a parent or who you have as a child or children, these are all things that can help us move better and work not on our kids but work with them. So it’s nice that it works.

William Stixrud:

And be close to them without being on top of them.

Ned Johnson:

Right, right. Yeah, that’s a good line, Bill.

Debbie:

Yes. my gosh, you guys, there’s just so many nuggets in here. I think, you know, just to wrap us up here, you know, just going back to teaching your kids an accurate model of reality. A lot of parents don’t even they haven’t taken the time to consider what it means to be happy for themselves. And so that’s why what you’re doing in this workbook, I think, is so important, because when we work on ourselves in this way. And that’s what so much of what I do, a tilt is helping parents kind of look at themselves. It changes everything. And it’s like, we have to like, turn the spotlight on ourselves to do this. And so I just want to name the workbook again, so listeners can go check it out. Again, it’s called The Seven Principles for Raising a Self-Driven Child, a workbook. It is out today as this episode drops, and I will have an extensive show notes page where I’ll share our previous interviews. I’ll share that conversation with Donna, as well as her awesome book, Is This Autism, which is phenomenal, and any other resources that came up. And I just want to say congratulations to both of you and thank you so much for everything you shared today.

Ned Johnson:

Thanks Debbie.

William Stixrud:

It’s a complete pleasure. Congratulations on all you’re doing too, Debbie.

Do you have an idea for an upcoming episode? Please share your idea in my Suggestion Box.